Know their story

I sighed inside as normally easy-going Jeremiah acted up for the fifth time that period. His behaviour was out-of-control and he had quickly taken the class with him to the point where no one was paying attention any longer. This was a fourth grade class, and I was a minority among hundreds of African-American students and teachers. Most of my students lived in government housing and tales of shootings, arrests, and drugs peppered their conversation every morning before school. I had been “adopted” by some veteran teachers who gave me tips and ideas on how to discipline while also sharing their stories of marching for equal rights in the 60s and being hosed down by the fire trucks during their peaceful protests. I was ashamed for my “whiteness,” but also very humbled that they were willing to come alongside and support me at the start of my teaching career.

“Jeremiah, come with me,” I insisted after his third warning. “We are going to call your mother.” His surprised face and hurt eyes showed me he was disappointed in himself, but my repeated warnings had only resulted in his behaviour worsening. I picked up the phone outside the classroom. As I began to dial, Jeremiah unbuttoned his shirtsleeve and pulled it up over his forearm. My stomach churned as I saw the imprint of an iron on his arm—each steam hole represented by a blister. “What happened?” I asked as tears rose up in my eyes. His eyes shifted away as he mentioned the iron had fallen on his arm while ironing at home. But the imprint of the iron was too deep and too well-placed to be a glancing burn—and so instead of calling his mother, I contacted Social Services.

In an instant, Jeremiah’s rude and obnoxious behavior was explained. I understood he was reacting to his physical and emotional pain in the only way he knew how and it was a cry for help.

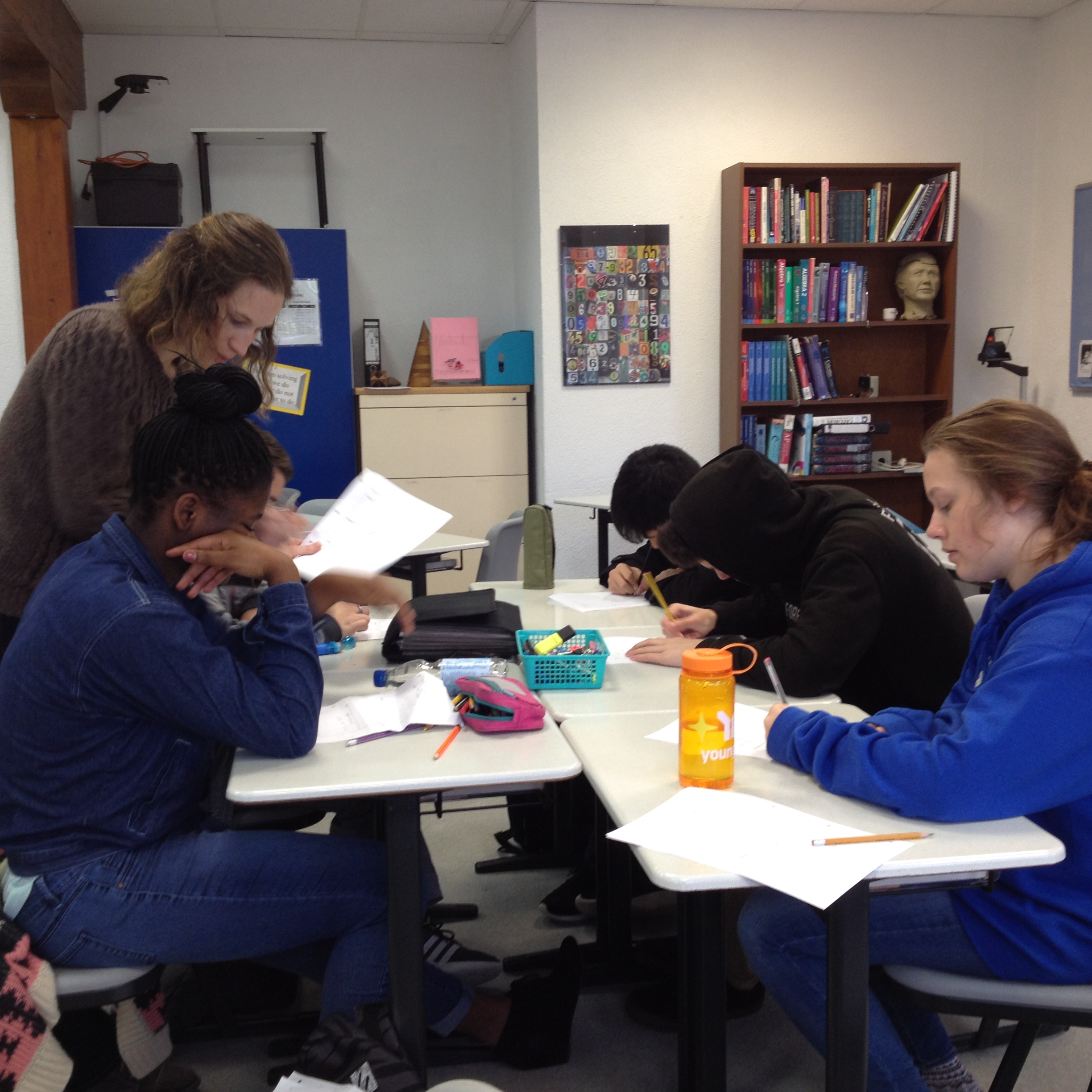

When we teach, do we know our students’ stories? More importantly, if we are teaching cross-culturally, as I was, do we know the culture our kids come from, what values are important in that culture, what challenges they have overcome, and what has shaped their behavior in the classroom? Would knowing this change our frustration with them into an understanding and care?

How will we learn their stories if we do not ask for them? Once we know, are we willing to take the time to adjust our attitudes and teaching to support our students’ learning?

One of my own children had a teacher who did exactly that. At the beginning of the year meeting, he said that he was sending a letter to each parent asking for a short summary of their story. Here is a copy of that email:

First order of business for me is getting to know my students, and this is something you can help me with. Some people love English class and for others it is a character-building experience. Furthermore, so many of our students come from diverse schooling backgrounds that I can’t make any assumptions about them. Could you write me a brief paragraph about your son or daughter’s schooling experience in the past? This shouldn’t be comprehensive, but rather a chance for you to tell me anything you think I really ought to know about your child for this school year. If that is too vague, perhaps you could tell me one thing you think your child may enjoy about English class and one area he or she may find challenging.

I filled out this questionnaire about my son, and the teacher took the time to really absorb this information. He cared about my son’s story. As a result, he was able to adjust his teaching in a way that ended up being so transformational that my son later described the experience in his college application essay.

If we do not learn our students’ stories then we risk perpetuating their pain and not providing them the assistance they need to process their past and move on with hope for their future. Learning their stories can be transforming for us as we begin to understand why they are behaving as they are, and meaningful for our students as we respond and teach to them in light of their stories.

What steps can you take to learn your students’ stories?

Debbie Kramlich, Ph.D. candidate

TeachBeyond, Thailand.

Debbie Kramlich is finishing up her Ph.D. in Educational Leadership in International Theological Education. As a part of this process, she has spend time studying transformative learning theory. This is the first in a series of articles on the teacher’s role in transformative learning. If you have a question or comment for Debbie, you can reach her by e-mailing onpractice@teachbeyond.org.