The Gifts of Language Learners

“I missed the bus.”

“I spilled my coffee.”

“My dog died.”

“The weather is bad.”

“I fought with my mum.”

“More. What else could be wrong?” My Hungarian teacher urged the class to list more and more things we could complain about when asked “How are you?” by a Hungarian.

I trust you not to form an opinion of Hungarian culture based solely on this story. But I want to reflect on how I felt as a language learner in that classroom.

Mainly I felt discouraged. God called me overseas to be a light in a dark place, to share the hope of Jesus with people who are hopeless. How could I be a blessing, when all I was learning in language class was how to complain?

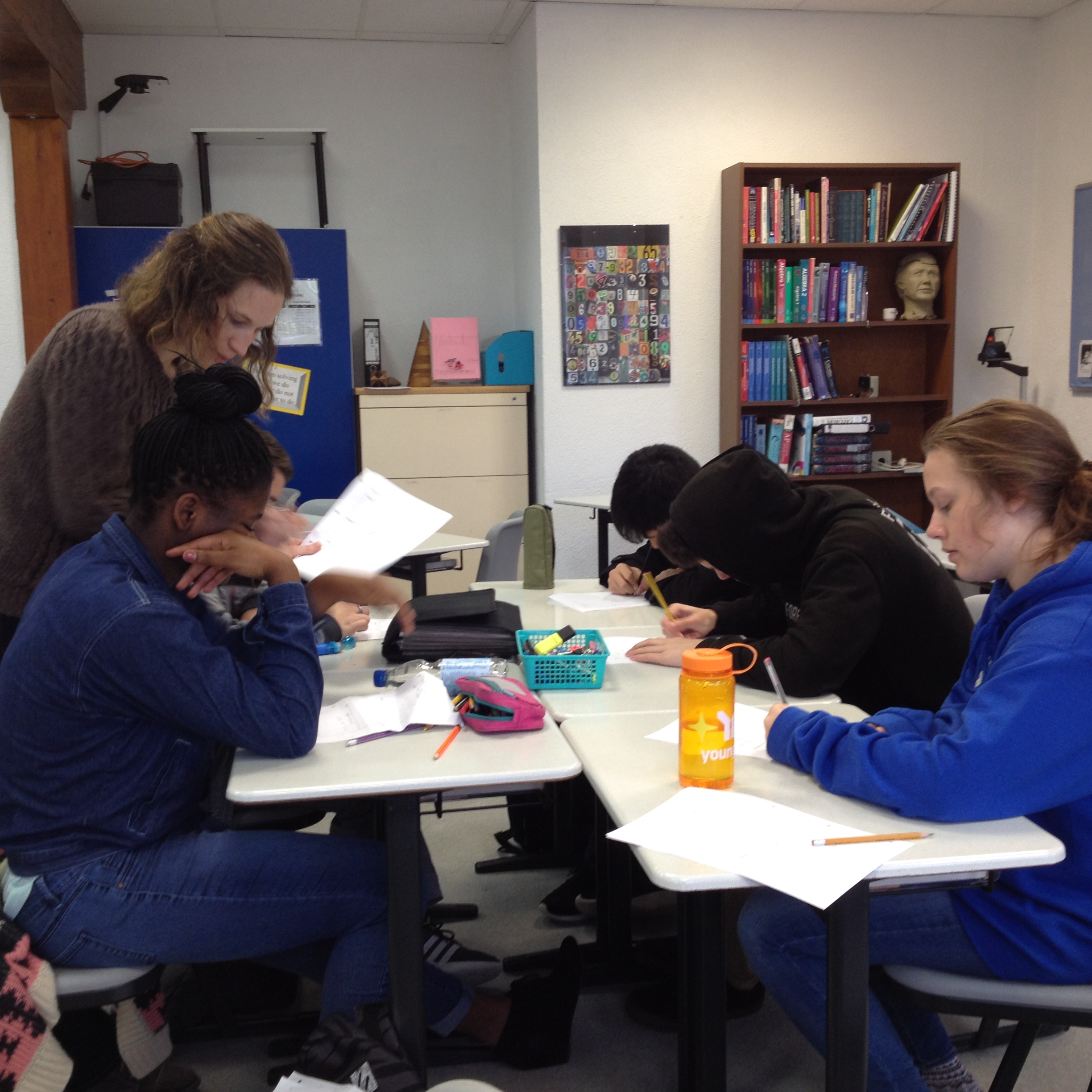

We bring the habits and blind spots of our culture into our classrooms. The more we become aware of our cultural tendencies and biases, the better we will be able to teach students who come from different cultures. As Christian teachers, we’ve thought carefully about how biblical worldview shapes our interactions with our students and colleagues. But we may not have thought about how our Christian faith speaks specifically to language teaching and learning.

The Gift of the Stranger

I want to offer some thoughts from a book called The Gift of the Stranger: Faith, Hospitality and Language Learning[1], a work I recommend to all language teachers–foreign or mother-tongue, all who find themselves as learners in a foreign culture, or all who welcome others into their own culture—in short, nearly all of us in TeachBeyond!

I want to offer some thoughts from a book called The Gift of the Stranger: Faith, Hospitality and Language Learning[1], a work I recommend to all language teachers–foreign or mother-tongue, all who find themselves as learners in a foreign culture, or all who welcome others into their own culture—in short, nearly all of us in TeachBeyond!

The book addresses the questions I faced in that Hungarian language classroom: How do we decide what to teach? “Further, what does such a choice imply about the kinds of persons we want our students to be when they are abroad [or interacting with a foreigner in their home culture]?[2]”

Grounded in the Biblical themes of reconciliation, justice and peace among nations, the authors “propose that foreign language education prepare students for two related callings: to be a blessing to strangers in a foreign land, and to be hospitable to strangers in their own homeland”[3]. Here, I will share some thoughts for language learners in a foreign land. In another article, I will explore how we offer hospitality to strangers in our homeland—and to students in our classrooms.

The Blessing of the Stranger

Smith and Carvill suggest that as strangers in a foreign land, we can offer three gifts to our hosts. Each of these have specific implications for how we teach the learners in our classrooms.

The gift of seeing what they do not see

We need to train students not to (only) look at the culture as a tourist looking through a camera lens, but to truly see. Not everything the learner sees is positive, but we can humbly call attention to the blind spots and help our hosts see themselves more clearly. Hungarians may not see anything problematic in a long list of complaints as a response to “How are you?” On the other hand, Americans may never have questioned why our typical response to the question is “fine,” when we even respond at all!

The gift of asking good questions

Learners often see cultural differences which can be difficult, or even impossible, to interpret without asking questions. We must teach students not only the grammatical skills to formulate questions, but the cultural competence to pose them respectfully. Students must also be equipped with enough of the history and context of their hosts to ask appropriate questions to uncover the “underlying meanings, values, and commitments of the target culture.[4]”

The gift of listening

Listening is a complex skill that needs to be developed carefully. We also need to teach students to be careful of thinking they understand too quickly. Sometimes we “understand” before we listen, interpreting differences through our own lenses, without truly listening for the answer to our question. It’s better to not understand than to misunderstand and reduce the person to a preconceived image; if we want to reach true understanding, we must “encounter and cherish the person from a different culture as a responsible, responsive person made in God’s image.[5]” This is uncomfortable to do, so students need help learning to be okay with the tension.

Conclusion

The famous love chapter of the Bible starts with the truth that “If I speak in the tongues of men and of angels, but  have not love, I am a noisy gong or a clanging cymbal.[6]” On the other side, we can meet the stranger with all the love in the world, but if we cannot communicate that love in a way that he or she can receive it—with words or not, with correct grammar or without—it will still sound like a noisy gong. We can certainly communicate love without words, but learning language is a gift to the people with whom we wish to connect; it is one of the ways we communicate love. Let’s not forget that truth in the language classroom.

have not love, I am a noisy gong or a clanging cymbal.[6]” On the other side, we can meet the stranger with all the love in the world, but if we cannot communicate that love in a way that he or she can receive it—with words or not, with correct grammar or without—it will still sound like a noisy gong. We can certainly communicate love without words, but learning language is a gift to the people with whom we wish to connect; it is one of the ways we communicate love. Let’s not forget that truth in the language classroom.

Hope Péter, M.A. in TESOL

LinGo English Enriched Schools Central European Coordinator

TeachBeyond

________________________________________

[1] Smith, David I. & Barbara Carvill. The Gift of the Stranger: Faith, Hospitality and Language Learning. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans Publishing Co, 2000. All quotes in this article come from this book.

[2] pg. 57.

[3] pg 58. Italics in the original.

[4] pg. 70.

[5] pg 73.

[6] 1 Cor. 13:1

Photo Credits: Conference. René Zieger, via Wikimedia.org, CC BY-SA 4.0. Gift of the Stranger, via amazon.com. Gong, Letsol, via Wikimedia.org. CC BY-SA 3.0.