Necessary Evils?

Why did you go into teaching? I can guess that it was not because you like to grade papers, clean your classroom or make phone calls home to parents. In fact, you might say those tasks are necessary evils of our work as teachers.

Have you ever stopped to consider how our Christian worldview informs how we work, particularly the tasks we don’t like. Most of us have wrestled with how a Christian worldview informs how and what we teach, but how does it affect the way we work?

When we consider Genesis 1-2, we can see that work was actually created before the fall. Adam was tasked with caring for the Earth and naming the animals. He was invited to not only enjoy God’s work of creation but to join Him in it by creating further order and beauty. Therefore, work is sacred; it is good. But as we know, just one chapter later, sin entered the world and one of the results of the breaking of Shalom, is that from that point on work is cursed. The earth now pushes back and makes it difficult for us to work it. Thorns and briars get in our way and now work is toil.

Likewise, in our classrooms we have moments when the educational process is so good. Our teaching is full of creativity and passion. Our students are having those “light bulb” learning moments that invigorate us. But we all know that our tasks each day also include grading papers, not to mention sorting out late assignments, collecting field trip forms that are mangled in the bottom of a book bag, and tidying up our classroom. I’m sure you can come up with your own list of necessary evils. Is there Redemption for those pieces of our work? Or do we merely have to put our hand to the plow and toil?

I would like to assert the things we consider as necessary evils could be means of grace. First, they remind us that the world is broken and that even in our classrooms we do not reign supreme. We need God’s help to create order and beauty. These mundane tasks can be worship unto him. Secondly, they also allow us to model for our students how to do those things we would rather not do. Lastly, if we seek the Lord for his help with chores we dislike, maybe it would also remind us to seek him in the tasks we do like and with which feel more confident, so that we may see his glory in greater ways. After all, Paul tells us in Colossians that we aren’t working for earthly masters, but “it is the Lord Christ you are serving[1].”

Here are a few practical ideas of how to be faithful in the unlikable duties,

- Ask colleagues how they accomplish those everyday jobs, and don’t be afraid to steal what works!

- Incorporate a new routine that makes these necessary evils much less annoying

- Set a timer, work hard until the timer is up and take a break and come back to it

- Put those tasks first, while you have enough energy to do them efficiently and well

- Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, ask God to help you in all parts of your work. And then go a step further and give thanks in whatever you do[2].

By October, we are solidly entrenched in the school year with all the work that it entails. May we find the grace to move past calling these mundane tasks “necessary evils” and embrace the opportunity to bring a little touch of God’s goodness, order and beauty into all parts of our work.

Christy Biscocho, M.Ed.

Teacher Education Services

TeachBeyond

Photo Credits: Gradebook. David Mulder, via Flicker. CC2.0. Adam

and Eve in the Garden of Eden, Johann Wenzel Peter, public domain. Prayer. via Shutterstock.

[1] Colossians 3:23-24 NIV

[2] Colossians 3:17 NIV

Thus a yearly curriculum plan will have far less detailed than a unit plan, which will be less detailed than a daily lesson plan.

Thus a yearly curriculum plan will have far less detailed than a unit plan, which will be less detailed than a daily lesson plan. determine how many days will likely be needed for students to reach these objectives. At this stage, you might consider the following:

determine how many days will likely be needed for students to reach these objectives. At this stage, you might consider the following:

Creating beauty can mean decorating a room or painting a picture, but it can also mean resolving conflicts so there may be beautiful and harmonious fellowship again. Creating beauty can also mean leading others to become beauty creators by exemplifying what it means to create beauty. God is the original beauty creator. When He created the earth, He was full of love, peace, and joy about what He was doing. As Christian teachers we are united with God and are able to teach with His characteristics. Being beauty creators means bringing love, joy and peace into our classrooms.

Creating beauty can mean decorating a room or painting a picture, but it can also mean resolving conflicts so there may be beautiful and harmonious fellowship again. Creating beauty can also mean leading others to become beauty creators by exemplifying what it means to create beauty. God is the original beauty creator. When He created the earth, He was full of love, peace, and joy about what He was doing. As Christian teachers we are united with God and are able to teach with His characteristics. Being beauty creators means bringing love, joy and peace into our classrooms. y. While little girls are practicing their newly found language skills, chattering away to whomever will listen, little boys are busy climbing on things and racing cars—delighting when there is a big crash with a lot of noise. Anyone who has ever worked with young children will attest to these obvious differences. And yet, despite these clear differences, our classrooms are often set up to treat both male and female learners the same. Why is this, and what can we do to address it?

y. While little girls are practicing their newly found language skills, chattering away to whomever will listen, little boys are busy climbing on things and racing cars—delighting when there is a big crash with a lot of noise. Anyone who has ever worked with young children will attest to these obvious differences. And yet, despite these clear differences, our classrooms are often set up to treat both male and female learners the same. Why is this, and what can we do to address it? .

.

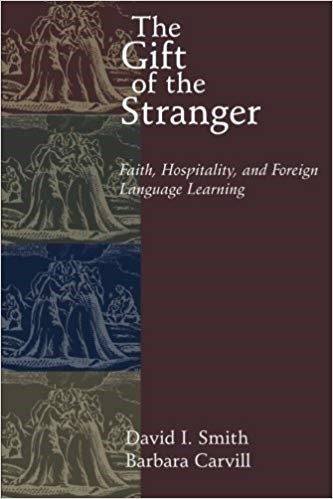

I want to offer some thoughts from a book called The Gift of the Stranger: Faith, Hospitality and Language Learning[1], a work I recommend to all language teachers–foreign or mother-tongue, all who find themselves as learners in a foreign culture, or all who welcome others into their own culture—in short, nearly all of us in TeachBeyond!

I want to offer some thoughts from a book called The Gift of the Stranger: Faith, Hospitality and Language Learning[1], a work I recommend to all language teachers–foreign or mother-tongue, all who find themselves as learners in a foreign culture, or all who welcome others into their own culture—in short, nearly all of us in TeachBeyond! have not love, I am a noisy gong or a clanging cymbal.[6]” On the other side, we can meet the stranger with all the love in the world, but if we cannot communicate that love in a way that he or she can receive it—with words or not, with correct grammar or without—it will still sound like a noisy gong. We can certainly communicate love without words, but learning language is a gift to the people with whom we wish to connect; it is one of the ways we communicate love. Let’s not forget that truth in the language classroom.

have not love, I am a noisy gong or a clanging cymbal.[6]” On the other side, we can meet the stranger with all the love in the world, but if we cannot communicate that love in a way that he or she can receive it—with words or not, with correct grammar or without—it will still sound like a noisy gong. We can certainly communicate love without words, but learning language is a gift to the people with whom we wish to connect; it is one of the ways we communicate love. Let’s not forget that truth in the language classroom.

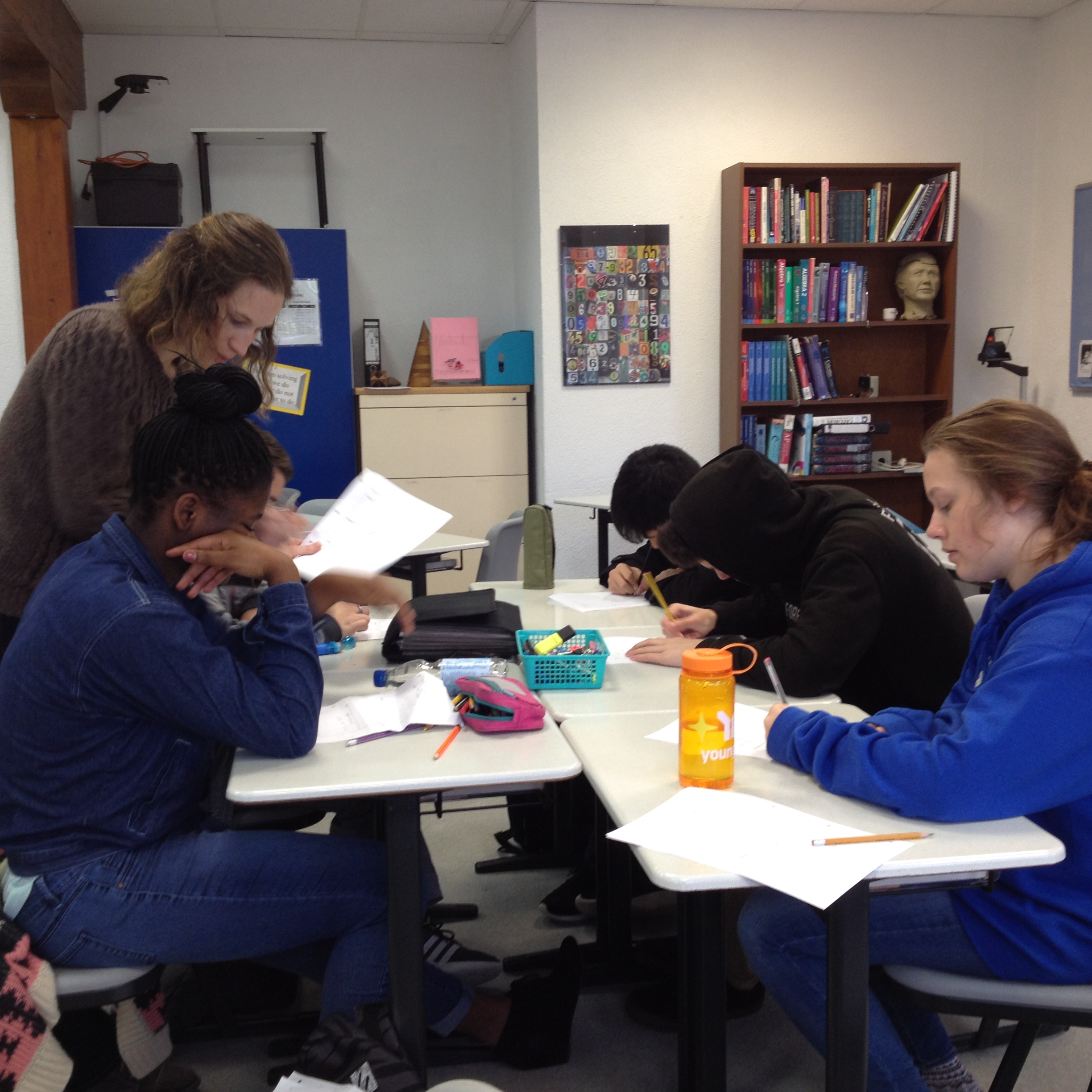

Whether you are a classroom teacher, administrator, counsellor, or support staff, you should be working as a team to support students with special needs. Having a team of people, whether it is two or ten, is important for several reasons. First, we all see things differently, have insight from different experiences, and hold different areas of expertise. Team members can learn from one another. Together they can develop better plans for addressing individual situations. A team has more resources from which to draw. Second, having a team helps with the emotional burden that can come from supporting struggling students. A team not only provides support for the specific student, but it also provides the support needed for the staff working with the student. A team can help us appropriately process emotions and frustrations. Do not let pride cause you to try to solve the problems on your own; build a team to support and pray for the student and for one another.

Whether you are a classroom teacher, administrator, counsellor, or support staff, you should be working as a team to support students with special needs. Having a team of people, whether it is two or ten, is important for several reasons. First, we all see things differently, have insight from different experiences, and hold different areas of expertise. Team members can learn from one another. Together they can develop better plans for addressing individual situations. A team has more resources from which to draw. Second, having a team helps with the emotional burden that can come from supporting struggling students. A team not only provides support for the specific student, but it also provides the support needed for the staff working with the student. A team can help us appropriately process emotions and frustrations. Do not let pride cause you to try to solve the problems on your own; build a team to support and pray for the student and for one another. Students with special needs want to be like everyone else. They don’t want to feel stupid, slow, forgetful, or outcast, but often they do. They lack confidence in trying new things because they may fail again. These students feel they are always scrambling to keep up with their peers. What many students learn intuitively, students with special needs need to be taught directly.

Students with special needs want to be like everyone else. They don’t want to feel stupid, slow, forgetful, or outcast, but often they do. They lack confidence in trying new things because they may fail again. These students feel they are always scrambling to keep up with their peers. What many students learn intuitively, students with special needs need to be taught directly.

Accept the challenge to join colleagues in thinking hard, discussing often, and praying fervently about this all too common stumbling block around suffering. How can we prepare our students with a theology of suffering that equips them to stand firm in the faith even when faced by “trials and tribulations of many kinds ” (5)? How can we facilitate discussions surrounding prayer that avoid the “Cosmic Sugar Daddy” trap? What messages are our lives sending to our students—both explicitly and tacitly—about suffering and disappointed expectations?

Accept the challenge to join colleagues in thinking hard, discussing often, and praying fervently about this all too common stumbling block around suffering. How can we prepare our students with a theology of suffering that equips them to stand firm in the faith even when faced by “trials and tribulations of many kinds ” (5)? How can we facilitate discussions surrounding prayer that avoid the “Cosmic Sugar Daddy” trap? What messages are our lives sending to our students—both explicitly and tacitly—about suffering and disappointed expectations?

about God restoring us – and through us others and His creation – as His image in Christ, who is the perfect image of God.

about God restoring us – and through us others and His creation – as His image in Christ, who is the perfect image of God. Howard Dueck (MA, Biblical Counselling), together with his wife Eileen, began their service with TeachBeyond in 1988 in Brazil, where Howard taught, counselled and was involved in leadership at the Gramado Bible College. He continued counselling and teaching when they moved to Germany. He is currently based near Winnipeg, Canada, and serves as the TeachBeyond regional director for Latin America and director for Beyond Borders (TeachBeyond’s education outreach to displaced persons).

Howard Dueck (MA, Biblical Counselling), together with his wife Eileen, began their service with TeachBeyond in 1988 in Brazil, where Howard taught, counselled and was involved in leadership at the Gramado Bible College. He continued counselling and teaching when they moved to Germany. He is currently based near Winnipeg, Canada, and serves as the TeachBeyond regional director for Latin America and director for Beyond Borders (TeachBeyond’s education outreach to displaced persons).