Transformational Principle 1

Last week I travelled for a few days. While I was gone, Dana transformed an old thrift-store desk into a beautifully restored antique. She worked hard to take it apart, scrub, sand, and paint it. Knowing that I love to put things together, she waited to finish it. When I got home, I spread out the doors, handles, nuts, and nails. I didn’t know how the pieces went back together: I had a basic idea, but there were brackets and strips of wood that I didn’t understand. What was the desk supposed to look like when it was together?

I needed help, I needed to know the design.

When your children sit down in your classroom, what are you after? When they come to you, what is your purpose? We know that we teach best when we have the end in mind.

The first of four TeachBeyond principles for Transformational Education helps us know where to go and how to get there: “We pursue transformation which aligns with God’s creative design while trusting the Spirit for complete transformation into the image of Christ.”

What does this mean for you today?

- We have a powerful purpose. We don’t just go through the curriculum. Our overarching purpose for each child is uncovering “God’s creative design.” We call out in each student a design rooted in the image of God (Genesis 1:27) and by God’s grace we encourage every student to become like Christ and develop the gifts and abilities God has given to accomplish His purposes (Ephesians 2:10).

- We pray for wisdom. As I needed Dana to show me how the pieces fit for the desk, we need God’s wisdom to help us understand how each child is designed, what each one can be as a unique and special person (Jeremiah 1:5). We ask the Lord to show us what each child might be, not just how they are.

- We pray for God to work. God, not the teacher, grows children (1 Corinthians 3:6). Just as Paul planted and Apollos watered, we contribute in some way to our students’ growth, but we cannot transform a child. This is God’s job. We can use best practices and pray for His grace, but the Holy Spirit transforms hearts and lives. We don’t. A wise transformational teacher once said, “We do much less than we think we do.”

- We respect each person. Since we are pursuing God’s creative design, we watch each child for hidden gifts and strengths. Then we give them opportunities to use and grow according to their gifts. We provide options for learning when we can so that each child grows toward the design God has for them. We celebrate each one’s giftedness and place in our class.

- We recognise two levels of transformation. The first is growing each child toward the best he or she can be through normal teaching practice. We give them education that changes their knowledge and abilities, helping each child to become the special person each is. But we are always mindful of pointing them to complete transformation in Jesus by knowing Him through faith and becoming a new creation (2 Corinthians 5:17).

- There is no end. Every child can continue to grow and learn, even if he or she has met the curriculum standards. Every child who knows Jesus by faith should continue to learn and grow toward the image of Christ. Faith in Christ is not our end goal, complete transformation to His image is—and this is a life-long process.

- We are not adequate to do this. As Paul says in 2 Corinthians 3:5, “Not that we are adequate in ourselves to consider anything as coming from ourselves, but our adequacy is from God.” We are servants of a new covenant, of the Spirit who gives life. The beginning of our work as a transformational educator is to be transformed ourselves by knowing we are also in need of the work of the Spirit in our lives. Perhaps the most important thing we can do for our students is to make sure we are letting God transform us.

As I studied the pieces of the desk and Dana told me how they fit, we were able to put together a beautiful, new desk out of an old one. In so much higher and deeper and wider ways, God will use you to pursue His design for each child, by His grace through the Holy Spirit. Each child can become more what God intends and we get to be a part of that.

Joe Neff, Th.M.

Coordinating Director of Education Services

TeachBeyond Global

Photo Credits: Desk. J. Neff, 2019. Girl. T. Peters, 2017. ble 2 Ac

I want to offer some thoughts from a book called The Gift of the Stranger: Faith, Hospitality and Language Learning[1], a work I recommend to all language teachers–foreign or mother-tongue, all who find themselves as learners in a foreign culture, or all who welcome others into their own culture—in short, nearly all of us in TeachBeyond!

I want to offer some thoughts from a book called The Gift of the Stranger: Faith, Hospitality and Language Learning[1], a work I recommend to all language teachers–foreign or mother-tongue, all who find themselves as learners in a foreign culture, or all who welcome others into their own culture—in short, nearly all of us in TeachBeyond! have not love, I am a noisy gong or a clanging cymbal.[6]” On the other side, we can meet the stranger with all the love in the world, but if we cannot communicate that love in a way that he or she can receive it—with words or not, with correct grammar or without—it will still sound like a noisy gong. We can certainly communicate love without words, but learning language is a gift to the people with whom we wish to connect; it is one of the ways we communicate love. Let’s not forget that truth in the language classroom.

have not love, I am a noisy gong or a clanging cymbal.[6]” On the other side, we can meet the stranger with all the love in the world, but if we cannot communicate that love in a way that he or she can receive it—with words or not, with correct grammar or without—it will still sound like a noisy gong. We can certainly communicate love without words, but learning language is a gift to the people with whom we wish to connect; it is one of the ways we communicate love. Let’s not forget that truth in the language classroom.

Whether you are a classroom teacher, administrator, counsellor, or support staff, you should be working as a team to support students with special needs. Having a team of people, whether it is two or ten, is important for several reasons. First, we all see things differently, have insight from different experiences, and hold different areas of expertise. Team members can learn from one another. Together they can develop better plans for addressing individual situations. A team has more resources from which to draw. Second, having a team helps with the emotional burden that can come from supporting struggling students. A team not only provides support for the specific student, but it also provides the support needed for the staff working with the student. A team can help us appropriately process emotions and frustrations. Do not let pride cause you to try to solve the problems on your own; build a team to support and pray for the student and for one another.

Whether you are a classroom teacher, administrator, counsellor, or support staff, you should be working as a team to support students with special needs. Having a team of people, whether it is two or ten, is important for several reasons. First, we all see things differently, have insight from different experiences, and hold different areas of expertise. Team members can learn from one another. Together they can develop better plans for addressing individual situations. A team has more resources from which to draw. Second, having a team helps with the emotional burden that can come from supporting struggling students. A team not only provides support for the specific student, but it also provides the support needed for the staff working with the student. A team can help us appropriately process emotions and frustrations. Do not let pride cause you to try to solve the problems on your own; build a team to support and pray for the student and for one another. Students with special needs want to be like everyone else. They don’t want to feel stupid, slow, forgetful, or outcast, but often they do. They lack confidence in trying new things because they may fail again. These students feel they are always scrambling to keep up with their peers. What many students learn intuitively, students with special needs need to be taught directly.

Students with special needs want to be like everyone else. They don’t want to feel stupid, slow, forgetful, or outcast, but often they do. They lack confidence in trying new things because they may fail again. These students feel they are always scrambling to keep up with their peers. What many students learn intuitively, students with special needs need to be taught directly.

Accept the challenge to join colleagues in thinking hard, discussing often, and praying fervently about this all too common stumbling block around suffering. How can we prepare our students with a theology of suffering that equips them to stand firm in the faith even when faced by “trials and tribulations of many kinds ” (5)? How can we facilitate discussions surrounding prayer that avoid the “Cosmic Sugar Daddy” trap? What messages are our lives sending to our students—both explicitly and tacitly—about suffering and disappointed expectations?

Accept the challenge to join colleagues in thinking hard, discussing often, and praying fervently about this all too common stumbling block around suffering. How can we prepare our students with a theology of suffering that equips them to stand firm in the faith even when faced by “trials and tribulations of many kinds ” (5)? How can we facilitate discussions surrounding prayer that avoid the “Cosmic Sugar Daddy” trap? What messages are our lives sending to our students—both explicitly and tacitly—about suffering and disappointed expectations?

Have you ever found yourself rushing through the last bit of lecture so that you can finish up before the bell rings? Calling out homework assignments as students trickle out the door? Ending in the middle of an activity because the specials teacher is waiting? If you are like most teachers, the answer to these questions is probably a resounding yes.

Have you ever found yourself rushing through the last bit of lecture so that you can finish up before the bell rings? Calling out homework assignments as students trickle out the door? Ending in the middle of an activity because the specials teacher is waiting? If you are like most teachers, the answer to these questions is probably a resounding yes. ficult or confusing in this chapter is… b/c… but I overcame my challenge by…

ficult or confusing in this chapter is… b/c… but I overcame my challenge by…

All of us can improve both our memory and our ability to transfer knowledge to unfamiliar situations with active effort. The most effective learning takes place when students are faced with desirable difficulty—a learning task that requires effort at a level slightly beyond the expected level for students.[2] Unfortunately, this effort is hard and most of us don’t naturally choose to do things the hard way. In fact, in their research, Brown, et al., discovered that most people revert to study patterns that require less effort even after experiencing greater learning using more difficult study techniques.[3] As fallen people, we want to believe that we can somehow get something for nothing—or as close to nothing as possible. We want to abandon our calling to cultivate in favour of an easier path.

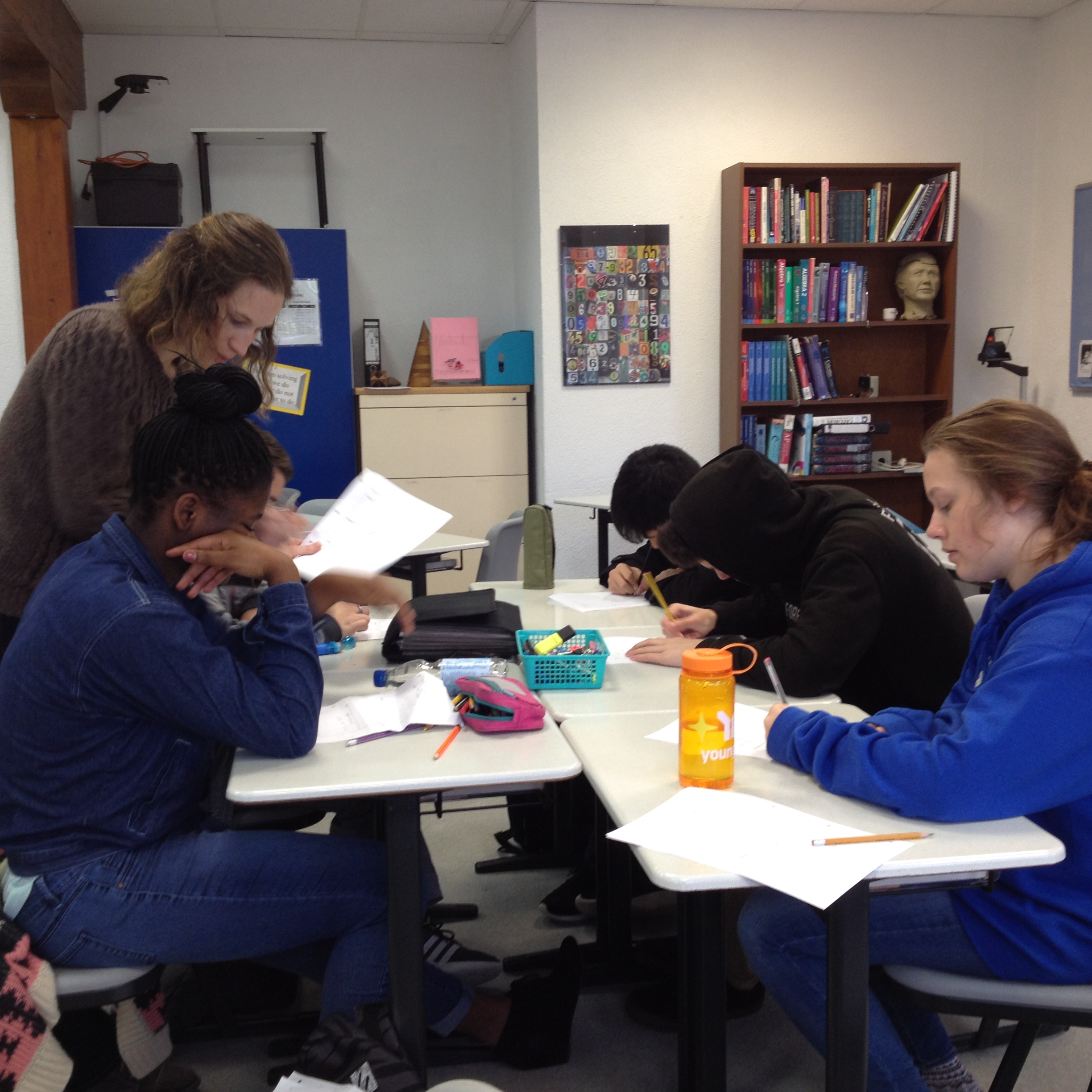

All of us can improve both our memory and our ability to transfer knowledge to unfamiliar situations with active effort. The most effective learning takes place when students are faced with desirable difficulty—a learning task that requires effort at a level slightly beyond the expected level for students.[2] Unfortunately, this effort is hard and most of us don’t naturally choose to do things the hard way. In fact, in their research, Brown, et al., discovered that most people revert to study patterns that require less effort even after experiencing greater learning using more difficult study techniques.[3] As fallen people, we want to believe that we can somehow get something for nothing—or as close to nothing as possible. We want to abandon our calling to cultivate in favour of an easier path. I’ve found that the hardest part for me in designing this type of learning activity is getting myself out of the way. My tendency is to want to jump in and direct the students, to help them discover the answer. I want to prevent them from taking wrong turns or making common mistakes. Unfortunately, when I do this, I am unwittingly preventing my students from doing the work of thinking themselves. I am hindering, rather than empowering, learning.

I’ve found that the hardest part for me in designing this type of learning activity is getting myself out of the way. My tendency is to want to jump in and direct the students, to help them discover the answer. I want to prevent them from taking wrong turns or making common mistakes. Unfortunately, when I do this, I am unwittingly preventing my students from doing the work of thinking themselves. I am hindering, rather than empowering, learning.

As teachers, we should help students see needs of those who can’t help themselves. Perhaps this is as simple as a daily look at the “news.” Maybe it is choosing books that expose students to the struggles of others. However we choose to do this, we may have to break out of our comfortable routines to help students see and care about justice.

As teachers, we should help students see needs of those who can’t help themselves. Perhaps this is as simple as a daily look at the “news.” Maybe it is choosing books that expose students to the struggles of others. However we choose to do this, we may have to break out of our comfortable routines to help students see and care about justice. As teachers, we can build activities into our curriculum where students can practice justice. Consider picking a project and committing to it for the year with bulletin boards and regular updates[2]. Or encourage your students to respond to a need in your own community. When you hear about injustice, help students to always ask, “What should we do?”

As teachers, we can build activities into our curriculum where students can practice justice. Consider picking a project and committing to it for the year with bulletin boards and regular updates[2]. Or encourage your students to respond to a need in your own community. When you hear about injustice, help students to always ask, “What should we do?”

For me, this happened last weekend as I watched a biopic called Queen of the Desert. I was fascinated by the life of Gertrude Bell (3rd from right), a Victorian debutante who ended up traversing Arabia and influencing the national borders post-Ottoman Empire. How had I never heard of this woman, this maker of kings? After all, I lived in that part of the world for four years. As soon as the movie ended, I had my phone out, researching to see how much of what I’d just seen was based in fact. I’ve now got my eye on a book of her letters that I’m hoping to find in the library on my next trip. My curiosity has been whetted; I’m eager to learn more.

For me, this happened last weekend as I watched a biopic called Queen of the Desert. I was fascinated by the life of Gertrude Bell (3rd from right), a Victorian debutante who ended up traversing Arabia and influencing the national borders post-Ottoman Empire. How had I never heard of this woman, this maker of kings? After all, I lived in that part of the world for four years. As soon as the movie ended, I had my phone out, researching to see how much of what I’d just seen was based in fact. I’ve now got my eye on a book of her letters that I’m hoping to find in the library on my next trip. My curiosity has been whetted; I’m eager to learn more. As teachers, we are privileged to spend a majority of our waking hours walking and living among our students.

As teachers, we are privileged to spend a majority of our waking hours walking and living among our students.

radically different from any other kind of school environment for this very reason: we exist to bring life! However, Christian schools and their members are not immune from conflict or the need for disciplinary actions. We all still have our struggles; it is the way in which these are handled that makes the difference in our schools.

radically different from any other kind of school environment for this very reason: we exist to bring life! However, Christian schools and their members are not immune from conflict or the need for disciplinary actions. We all still have our struggles; it is the way in which these are handled that makes the difference in our schools. God’s grace? How do we encourage students to move forward? Have we considered how the student might see themselves in light of the discipline? Staff should equip the students to address problems for themselves for the future, helping students consider what Scripture says.

God’s grace? How do we encourage students to move forward? Have we considered how the student might see themselves in light of the discipline? Staff should equip the students to address problems for themselves for the future, helping students consider what Scripture says.

more surprisingly, I can still recount the first time I worshipped God in class. It was Biology 101. We were learning about the human body, and as I learned how this system worked with that system, I marvelled at the complexity and beauty of it all. I began to feel my heart lean toward Heaven. “What a wonderful Creator!” I wanted to yell. I did restrain myself, but that is the day I decided to be a science teacher. I wanted to share that amazing experience with students so that they too could worship our wise God in the middle of class.

more surprisingly, I can still recount the first time I worshipped God in class. It was Biology 101. We were learning about the human body, and as I learned how this system worked with that system, I marvelled at the complexity and beauty of it all. I began to feel my heart lean toward Heaven. “What a wonderful Creator!” I wanted to yell. I did restrain myself, but that is the day I decided to be a science teacher. I wanted to share that amazing experience with students so that they too could worship our wise God in the middle of class. And how much fun it is to do this with students!

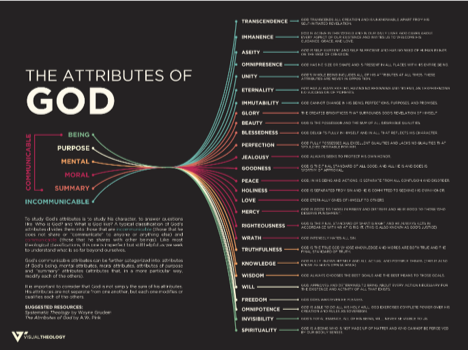

And how much fun it is to do this with students! What I hadn’t connected on my own was the way that balancing chemical equations was actually a reflection of God’s character. You see, one side of the equation has to balance with the other side. In a chemical reaction, nothing can be created or destroyed, it just changes form. Through her book I came to see that John 1:3 was describing this very law of nature, “Through him all things were made; without him nothing was made that has been made.” We can balance equations because nothing can be created or destroyed without God. He is the Transcendent Law Giver. As this truth hit me, I was able to lead my students to it the next day with questions like, “Why can we balance equations? Does this work every time? What if we could create and destroy matter? Who is the only one that can create and destroy?” In those few moments we were able to discuss and reflect on the character of God and hopefully that led to worship. I was recounting just how powerful and wise is our God. I can tell you I was worshipping!

What I hadn’t connected on my own was the way that balancing chemical equations was actually a reflection of God’s character. You see, one side of the equation has to balance with the other side. In a chemical reaction, nothing can be created or destroyed, it just changes form. Through her book I came to see that John 1:3 was describing this very law of nature, “Through him all things were made; without him nothing was made that has been made.” We can balance equations because nothing can be created or destroyed without God. He is the Transcendent Law Giver. As this truth hit me, I was able to lead my students to it the next day with questions like, “Why can we balance equations? Does this work every time? What if we could create and destroy matter? Who is the only one that can create and destroy?” In those few moments we were able to discuss and reflect on the character of God and hopefully that led to worship. I was recounting just how powerful and wise is our God. I can tell you I was worshipping!